Introduction

Aim:

- You will recognise the symptoms of the approaching stall, and know what avoiding action to take

- become familiar with the characteristics of the full stall, and learn how to recover with the minimum loss of height

- learn to avoid inadvertent stalling.

- The flying exercises will show what it feels like to stall.

What do we know?

- What is a stall?

- At what speed can a stall occur?

- Do all gliders stall?

- When is a stall dangerous?

Theory

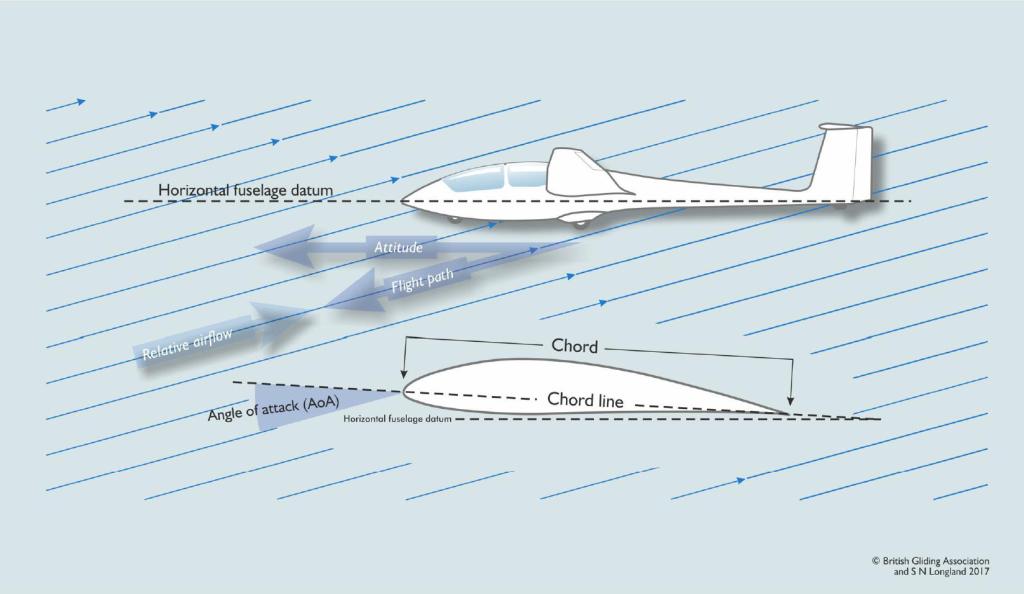

Terminology and References

Terms

- Horizontal Fuselage Datum

- Attitude

- Chord

- Chord Line

- Note how the Chord Line can be altered by the control surfaces

- Flight Path

- Relative Airflow

- Angle of Attack (AoA): angle between the relative airflow and the chord line.

Lift, and what affects it

The Wing must generate sufficient Lift to carry the Weight of the glider.

The amount of lift produced by a wing is affected by:

- Aerofoil’s Camber (overall shape)

- Wing Area

- Airflow Speed

- Angle of Attack

Factors affecting Airflow Speed

- Things we control:

- Change of Attitude

- Drag (use of Airbrakes, Flaps)

- Other things, beyond our control:

- Horizontal gusts

- Wind sheer

- Wind gradient

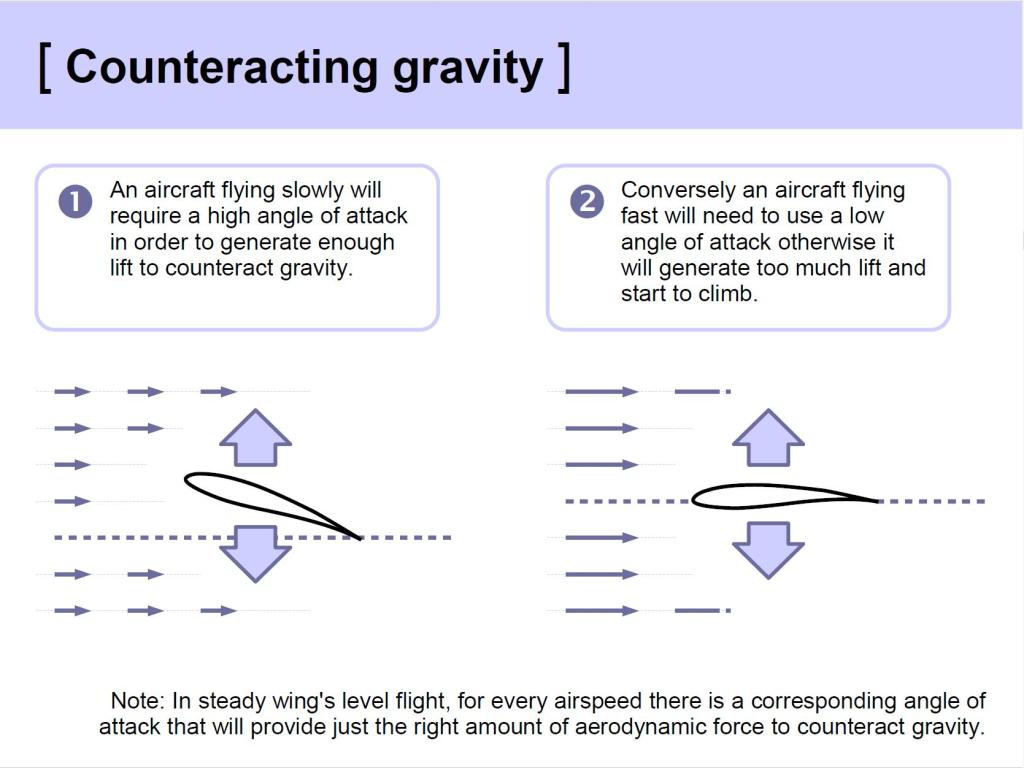

The Angle of Attack

For each Speed, there is a specific Angle of Attack that generates the required Lift:

- At high speed, a low AoA generates sufficient lift

- In slow flight a high AoA is necessary

At slower speeds, the required lift can be generated by increasing the AoA – but there is a limit: The Critical AOA.

The Critical Angle of Attack

- The AoA at which the maximum amount of lift is produced at a given airspeed

- Beyond which:

- Lift reduces (sometimes sharply)

- Drag continues to increase.

- It is

- Aerofoil specific

- Typically c. 15 degrees

Flight Path and Pitch Attitude

Flight Path: the direction in which the glider is travelling

Pitch Attitude: the direction in which it is pointing, relative to the horizontal

A glider will stall in any attitude, and at any speed, if the AoA reaches the Critical Angle.

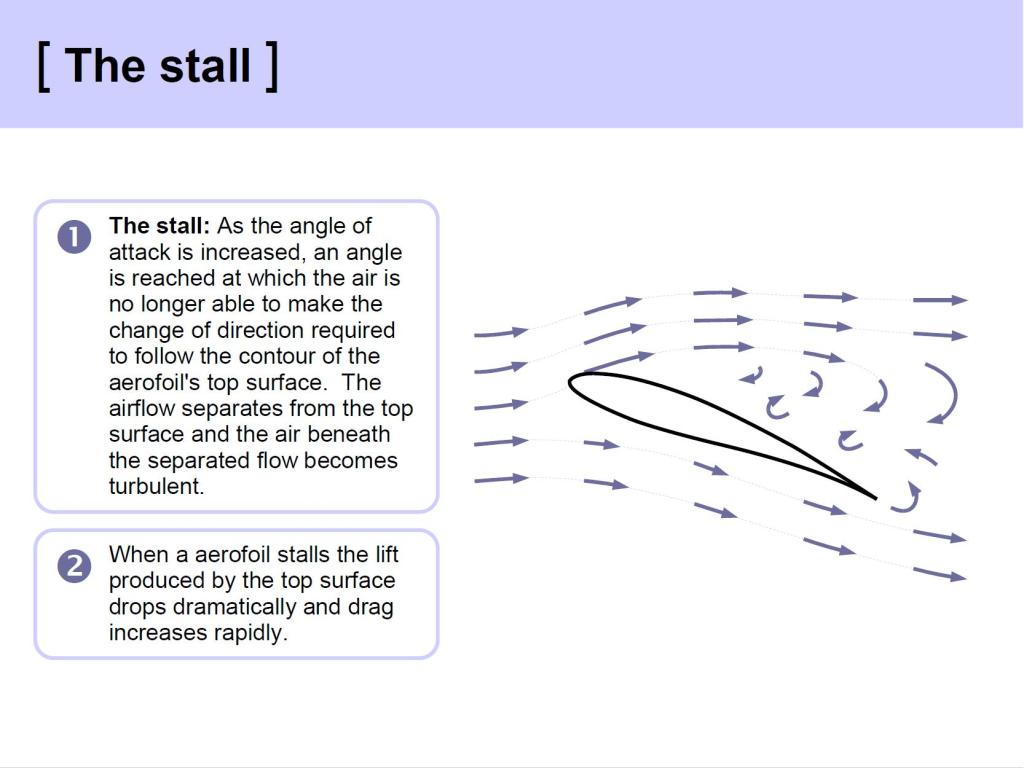

How a Stall occurs

As the AoA increases, turbulence initially forms at the wing root trailing edge, then progressively extends outwards and forwards.

When at the stall:

- The upper airflow breaks away becoming turbulent:

- Lift is lost

- Drag increases

- Weight is not supported

Stalling Speed

- Stalling Speed is the speed at which the wings will stall.

- A ‘higher stalling speed’ means the glider must fly faster to avoid stalling.

The Stalling Speed depends on

- Airspeed

- Wing loading

- Weight

- Vertical accelerations:

- Changes in direction: Turning, pulling out of a dive

- Cable tension in a winch launch.

- Contamination

- Bugs, Rain, Dirt

- Use of Airbrakes (reduces the effective wing area, and reduces the lift)

Further Points

Flying close to the stall, or partially stalled

- Inefficient

- Dangerous:

- close to the ground

- in thermals

Most gliders will stall in a progressive and smooth manner:

- Different aerofoils used near the tip

- Washout

- Drag and Sink increase markedly

The ailerons may continue to work

- Increasingly sluggish and ineffective

Aileron input close to the stall may result in very rapid roll in the opposite direction

- Down-going aileron (intended up-going wing) stalled

Secondary effect of rudder is more marked close to the stall

- A lot of roll with little yaw

Elevator may fail to raise the nose

Or the nose may drop regardless of stick position:

- the most important symptom of a stall.

Airflow noise changes

- Quieter,

- or Louder

- or ‘different’

- Yaw may alter it too.

Buffet

- Separated airflow may create buffet (on tailplane)

ASI Flicker

Turbulent airflow across the static ports.

Symptoms

- Attitude: nose higher than ‘normal’

- Airspeed is slow or reducing

- Airflow noise is changing

- ASI is flickering

- Airframe buffeting

- The effectiveness of the controls is changing

- Unusual control positions for the phase of flight: the stick is further back than ‘normal’ / lots of out of turn aileron

- High rate of descent (for the attitude)

- Elevator ineffective

Recovery

Standard Stall Recovery:

- Ease the Stick straight forward to pitch the glider below the normal gliding attitude

- Allow speed to build to regain flying speed

- Roll wings level, or return to the required attitude for the phase of flight

- Height loss: Up to 300 feet

Prevention

In slow flight, subtle signs:

- Pitch Attitude

- Airspeed

- Controls Response

- Controls Position

- Airflow Sounds different

Recovery:

- Ease the back pressure on the stick.

- Ask yourself: Why did it happen? Are you paying attention / flying fast enough for the conditions?

- Height loss: Less than 30 feet.

Unaccelerated, or 1G, Stalls

Stalls which occur without increasing the Wing Loading.

- May occur at speeds above the ‘1G Stall Speed’

Examples of Unaccelerated Stalls:

- Mushing Stall

- Stall without a nose drop

- Requires more ‘stick forward’ movement to recover than a stall with nose drop.

- Stall with a nose drop

- Stall with a wing drop

- recover after first regaining speed

- level wings with coordinated aileron and rudder

- ease out of the dive

- Stall with Airbrakes (or Spoilers) open

- Stalling speed is higher

- Stall may be very sudden, and steep

- Recovery: includes closing the Airbrakes or Spoilers

Accelerated, or High G, Stalls

- The glider will stall at any speed above the ‘normal’ 1G stall speed if:

- the Angle of Attack is high enough

- you pull enough G (Wing Load)

- They occur quickly

- Have fewer warnings

Examples of Accelerated Stalls:

Stall in a Turn

- Controls likely to be in unusual positions

- Recovery: as per Stall with Wing Drop

- Prevention: ease the back pressure on the stick

Stall in Climbing Attitude

- As if climbing into a thermal turn at speed, or after experiencing a winch launch failure during the climb

- Nose drop may be the first symptom

- Stall will be severe

- Recovery still requires the stick to go forward

- Prevention:

- monitor ASI;

- take prompt recovery action after a winch launch failure.

Stall in a Steep Turn

- Symptoms, such as buffet, appear at higher speed than a 1G stall.

- Recovery:

- ease the back pressure on the stick.

- in very steep turns, reduce bank before re-establishing the glider in the turn

- Prevention:

- monitor ASI, allowing for a higher stall speed

- ease back pressure on stick

- Steep turns require higher speed.

‘High Speed’ Stall

- The glider will stall at speeds above the unaccelerated stall speed if the G load is increased – e.g. when recovering from a stall or a spin too quickly, even if

- the wings are level,

- the glider is in an attitude at or below the normal gliding attitude.

- Stall may be more dramatic than the 1G stall

- Recovery: Standard Stall Recovery, but be careful to ease back on the stick during the recovery.

- Prevention: recover from the previous event carefully.

Prevention and Recovery is the same as Unaccelerated Stalls.

Sensations in a Stall

Reduced G as the nose drops.

- Is reduced G a symptom of a stall?

Recap

How much height might you lose in a stall?

How much height would be lost if a stall is prevented?

What are the symptoms of a stall – before the stall? When stalled?

How many stall symptoms are required before taking prevention or recovery action?

Can you stall when flying above the glider’s stated stall speed?

What is the ‘Standard Stall Recovery’?

TEM (Slow Flight)

Threats

Student Pilot adverse reaction

Mitigation:

- Instructor prepare and brief student appropriately & monitor them carefully.

Student Pilot fails to, or overreacts, at recovery

Mitigation:

- Instructor Monitor & take over promptly.

Collision

Mitigation:

- HASSLL checks: (Height (set minimum to start and finish), Airframe (Max Manoeuvring Speed), Security, Straps, Location, Lookout).

- Maintain Lookout throughout the exercise.

Errors

Running out of height for an appropriate circuit.

Mitigation:

- Monitor height and position.

Allowing a stall to develop.

Mitigation:

- Be prepared to recover immediately if a stall appears imminent.

TEM (Stalls)

Threats

Student Pilot adverse reaction

Mitigation:

- Instructor prepare and brief student appropriately & monitor them carefully.

Student Pilot fails to, or overreacts, at recovery

Mitigation:

- Instructor Monitor & take over promptly.

Collision

Mitigation:

- HASSLL checks: (Height (set minimum to start and finish), Airframe (Max Manoeuvring Speed), Security, Straps, Location, Lookout).

- Maintain Lookout throughout the exercise.

Errors

Running out of height for an appropriate circuit.

Mitigation:

- Monitor height and position.

Allowing a spin to develop at an inappropriate time or height.

Mitigation:

- Be prepared to recover anything that occurs, immediately.

Flight Exercises (Slow Flight & Stalls)

Summaries of the exercises to be flown:

Slow Flying

- HASSELL, raise the nose slightly, note symptoms, recover.

- Student attempt.

Stall without a nose drop (Mushing stall)

- HASSELL

- Raise the nose slightly, entering slow flight, continue to slow.

- Identify symptoms of the stall, stabilise glider in the stall, note high rate of descent.

- Recovery.

- Student attempt.

Stall with a nose drop (Straight stall)

- HASSELL

- Raise the nose slightly, entering slow flight, continue to slow.

- Initiate stall (stick held back).

- Recover (stick forward), smoothly to avoid secondary stall.

- Student attempt (aim for c. 20 degrees nose high).

Stall with a wing drop

- HASSELL

- Repeat the stall, provoke a wing drop (with rudder).

- Recover (regain speed, level wings, recover from dive).

- Student attempt (initially the recovery, then the stall and recovery).

Stall in landing configuration

- HASSELL

- Repeat the stall, with undercarriage down, and airbrakes (or spoilers) open.

- Note the (different, or lack of) symptoms, and the higher stalling speed.

- Recover (noting the need to also close the airbrakes or spoilers).

- Demonstration only, or Student attempt?

Lack of effective elevator at the stall

- HASSELL

- Dive to 55-60kts. Pull up into a steepish climb and wait for the stall.

- As the nose drops, move the stick fully back and knock it against the stop a few times, to demonstrate it has no effect of raising the nose.

- Recover (noting the stick must be moved forward to unstall the glider).

- Demonstration only.

Differences between stalling and reduced G

- HASSELL

- Dive to 55-60kts. Pull up into a 20-30 degree climb and wait for the stall.

- When stalled, note the sensation, and any stall symptoms including ineffective elevator.

- Recover, to now look at reduced G.

- Repeat the acceleration and climb as before.

- About 5kt above the previous stall speed, push over to create the sensation of reduced G. Note the glider responds to the controls and is not stalled, and raise the nose as it drops past the horizon.

- Optionally repeat the exercise to show the (dramatic) effect of lowering the nose when reduced G is felt (ensuring you have sufficient height for the recovery).

- Demonstration only.

Stall in a turn

- HASSELL

- Perform an unaccelerated stall with nose drop, noting the airspeed at the onset of the buffet.

- Enter a normal turn, c. 30 degrees of bank, then slow gradually to the stall.

- Note the unusual position of the controls, required to maintain the attitude and angle of bank.

- Note the airspeed at the onset of buffet, compared to unaccelerated stall.

- Continue until the glider is stalled.

- Recover.

- Student attempt.

Stall speed increases in the turn

- HASSELL

- Perform an unaccelerated stall with nose drop, noting the airspeed at the onset of the buffet.

- Enter a normal turn, c. 20 degrees of bank, then slow gradually to the stall.

- Note the higher airspeed at the onset of buffet, compared to unaccelerated stall.

- Recover by relaxing the back pressure on the stick.

- Recover.

- Repeat at 40 and 60 degrees of bank.

- Note the increase in stall speed is not linear.

- Demonstration only at the early stages.

High speed stall

- HASSELL

- Perform an unaccelerated stall with nose drop, noting the airspeed at the onset of the buffet.

- Dive to 55-60kts, and pull up into a fairly steep climb.

- Wait for the nose to drop, and ease the stick forward as in a normal recovery.

- Ease the stick back to recover, and as soon as the nose stops pitching down, if the speed is below 55kts, pull the stick to the back stop.

- Wait – the glider will buffet and stalls at a higher speed. Note ASI reading.

- Recover normally.

- Demonstration only at the early stages.