Introduction

Aim: You will know a little about thermals, understand the rules for safe thermalling, and have a method to utilise them for lift.

There are many excellent references on thermalling techniques, so the emphasis here is on safety, with an introduction to finding and using them.

What do we know?

- Who has thermalled already?

- Why do we do it?

- Is it safe?

- How do you use a thermal?

What is a Thermal?

- A thermal is a bubble of rising air.

- Stronger lift in the centre, surrounded by descending air.

- Sizes vary, with cores c. 200m across in the UK.

- Vertical speeds vary.

- They can be close together, or far apart.

- You may arrive at the bottom, in the middle or at the top.

- There may be a cloud on top,… or nothing to indicate their presence.

- They drift downwind.

How do they form?

Thermals are created by temperature differences on the surface.

- Typically the sun heats the ground (Radiation)

- Variations on the ground cause areas to warm up at different rates

- Warmer areas on the surface create warm air above them (Conduction)

- Warm air rises (Convection)

How do we find them?

Look up for signs of their presence

- Cumulus clouds

- Whisps forming

- Other gliders circling

- Soaring birds circling or hovering

Look down for their triggers

- Warm patches

- Sunshine

- Sun facing slopes

- Dark surfaces (soil, vegetation)

- Wooded areas (late pm)

- Temperature differences

- Water

- Edge of towns

- Adjacent Dark / Light surfaces

- Others

- Movement e.g. Farming

- Upwind of your current thermal

Why do we use them?

For lift.

- Sustains our flight, or extends the circuit.

- Allows cross-country soaring.

- Competitive racing.

Climb rates (in the UK) range from 0 to “10 up”, which is 10 knots (5 m/s) vertically, approximately 1,000 feet per minute. Climbing at 2 knots (in the UK) is OK – more is better.

Zero indicated means you’re staying up, which may be good enough.

Lookout & Thermalling Rules

This briefing is a subset of the knowledge that is available – refer to:

Lookout in a Thermic Sky

The presence of thermals creates traffic hot-spots

- Vertically

- Laterally

Collision Risks arise from

- Objects we can’t or don’t see

- Objects which do not get our attention

So we must actively look for gliders:

- in the thermal

- joining the thermal

- in our path when we leave the thermal

Pulling Up

- High risk of Collision:

- Horizontal speed slows rapidly

- Vision above and behind is inadequate

Diving Away

- High risk of Collision:

- Horizontal speed will change

- Vision below and behind is impossible

Thermalling Rules

Joining a Thermal

- Gliders already established in a thermal have the right of way.

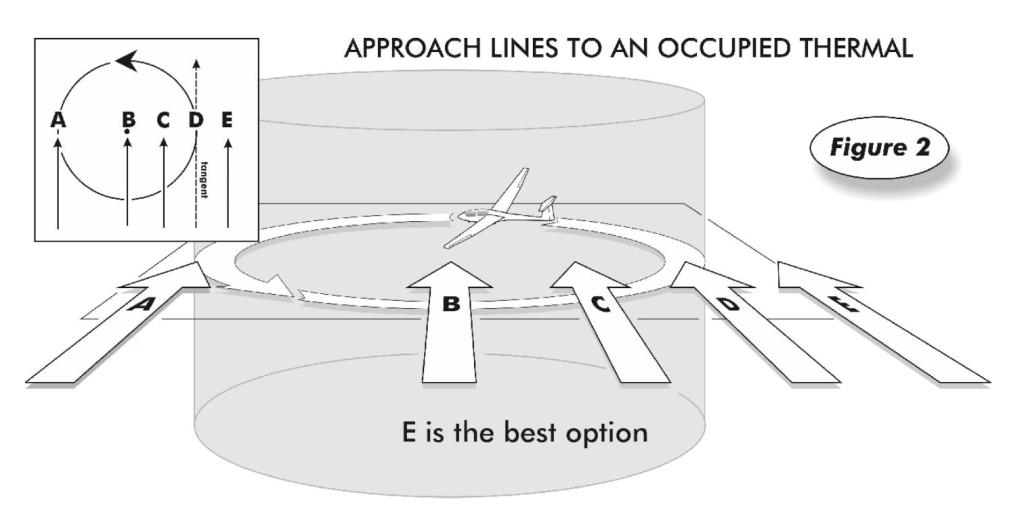

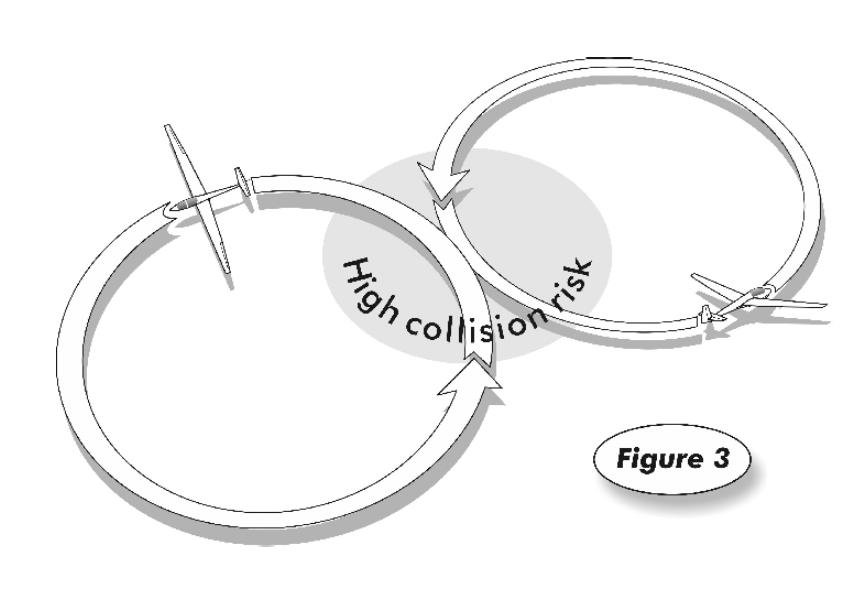

- All pilots shall circle in the same direction as any glider(s) already established in the area of lift.

- If there are gliders circling in opposite directions, the joining gliders shall turn in the same direction as the nearest glider (least vertical separation).

- The entry to the turn should be planned so as to keep constant visual contact with all other aircraft at or near the planned entry height.

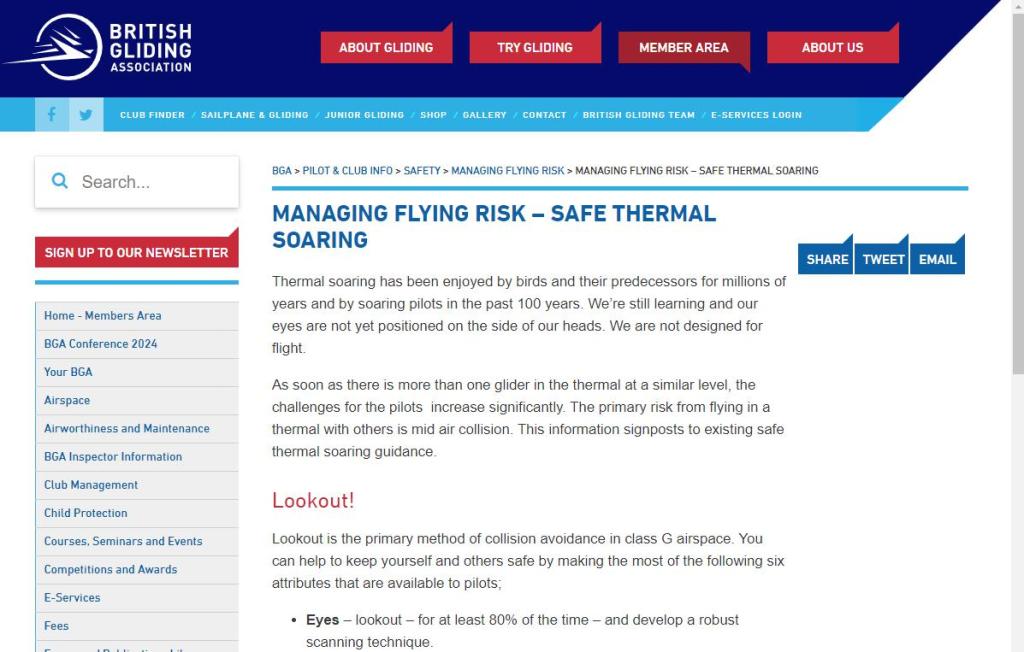

- The entry shall be flown at a tangent to the circle such that no aircraft already turning will be required to manoeuvre to avoid the joining aircraft.

Sharing a Thermal

- Pilots shall adhere to the principle of see and be seen.

- When at a similar level to another aircraft, never turn inside, or point at, or ahead of it, unless you intend to overtake and can guarantee safe separation.

- If, in your judgement, you cannot guarantee adequate separation, leave the thermal.

- Look out for other aircraft joining or converging in height.

Leaving a Thermal

- Look outside the turn and behind before straightening up.

- Do not manoeuvre sharply unless clear of all other aircraft.

Approaching to Join

Why is E the best way to approach an occupied thermal? Assume the glider illustrated is already there.

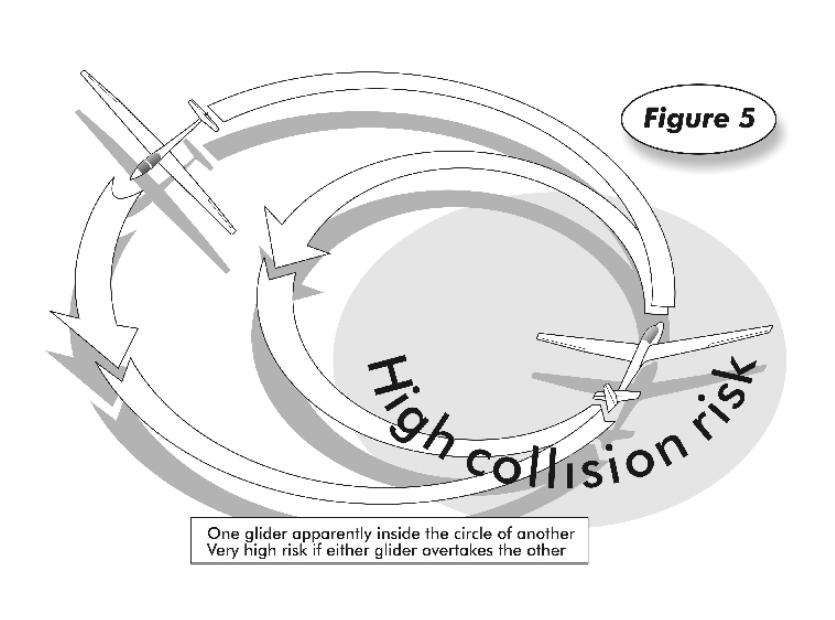

Overlapping Circles

Overlapping circles are very risky. Three scenarios:

Even if not centred, safety is the priority.

A method to exploit Thermals

Background:

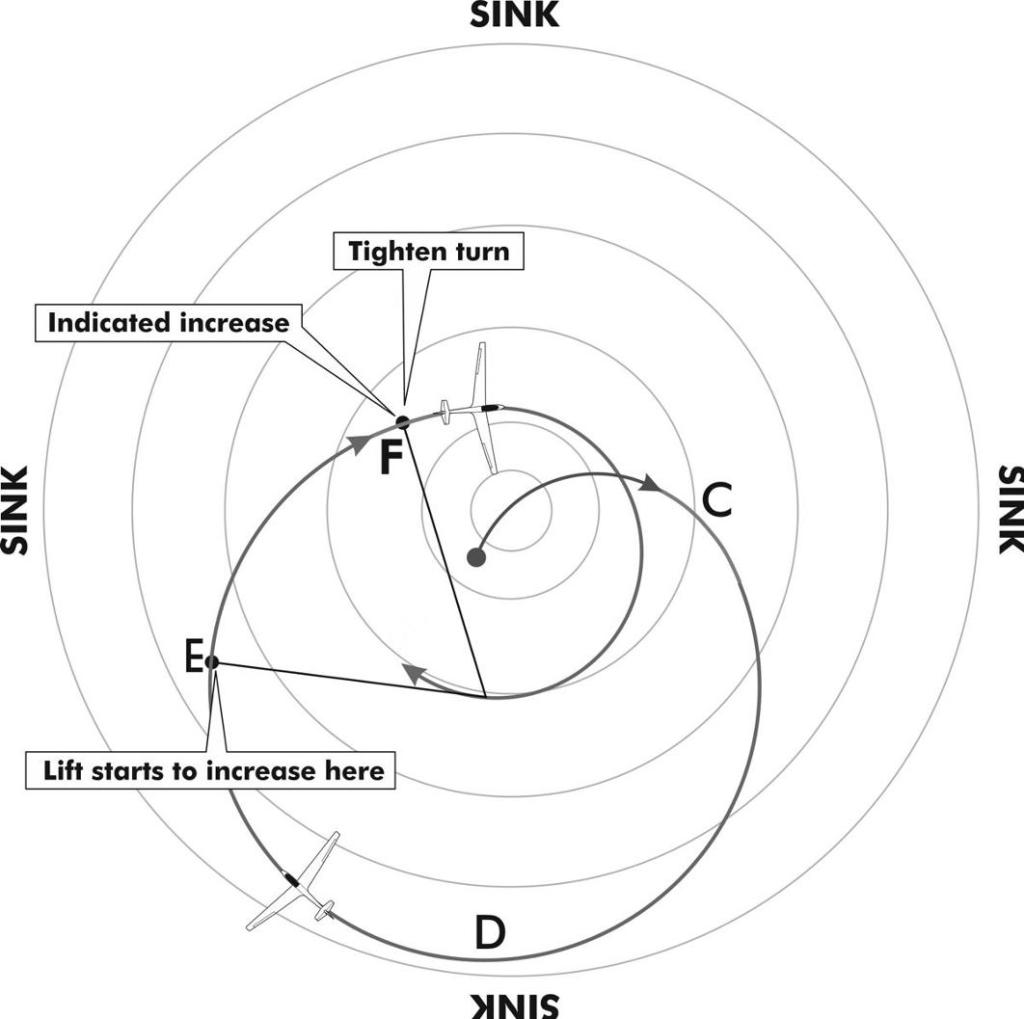

- Average (target) time to complete a full circle in a thermal is 15-20 seconds

- The typical mechanical variometer will indicate lift/sink about 3 seconds after the event

- That’s approximately 60 degrees late.

- This may help you to build a mental picture of where the lift is, and to move your circle appropriately.

- “Only a fool flies through the same sink twice” G Dale.

A simple method, based on vario lag:

- Fly a properly banked thermal turn all the way round: 40 degree bank (if you have the coordination to do so)

- Less lift (C) indicated: Reduce bank by c. 15 degrees

- More lift (F) indicated: Increase bank

- Visualise by “following the vario (needle)”, using it to guide your angle of bank.

- Judge 45 degrees by reference to the corner screws on most instruments: align them with the horizon.

Cloud Streets

- As a thermal drifts downwind, its heat source can generate another thermal to replace it.

- These thermals can join, creating a line of cloud, aligned for many kilometres, downwind from the original source.

- Their rising and sinking air, linked with fresh energy from the sun on the ground either side of them, and their own shadows, can create self-perpetuating columns of rising air along the length of the street.

- These attract pilots flying cross-country, focused on height and speed.

- Beware the potential for collision, especially just below cloud base.

Recap

- What is dangerous about thermalling?

- How do collisions occur?

- What are the rules for joining an occupied thermal?

- And if there are gliders circling in different directions?

- Should you focus on circling efficiently or cautiously?

- Is it safe to dive out of a thermal to avoid the sink?

- Is it sensible to thermal at half a knot?

TEM

- Collision: Lookout! Especially before joining and manoeuvring.

- Drift away from the Airfield: Ensure the climb is worth the drift.

- Climb into controlled airspace: use a GPS, and maintain awareness.